One proposal put forwards in CERN’s search for its next particle accelerator to succeed the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), due to be retired in the 2040s, is the Compact Linear Collider (CLIC).

This proposed accelerator already has a long history, and the collaboration behind it recently submitted input to the European Strategy for Particle Physics Update (ESPPU) to be considered as CERN’s flagship accelerator in the post-LHC era.

In this interview, CERN’s Steinar Stapnes, head of the CLIC project, explains the accelerator’s background, how it would contribute to new physics, and why it is a good candidate to be the next flagship collider.

You can read similar interviews with representatives of the Future Circular Collider (FCC) here, and the Muon Collider here, two other proposed future accelerators. You can also read an interview with a group that recently published a comparison study of six of the proposed future accelerators here.

*This interview was carried out before the electron–positron Future Circular Collider (FCC-ee) was announced, on 12 December, as the preferred option of the European Strategy for Particle Physics (ESPP) to be CERN's next flagship collider. Read more about the announcement here.

What is the CLIC project?

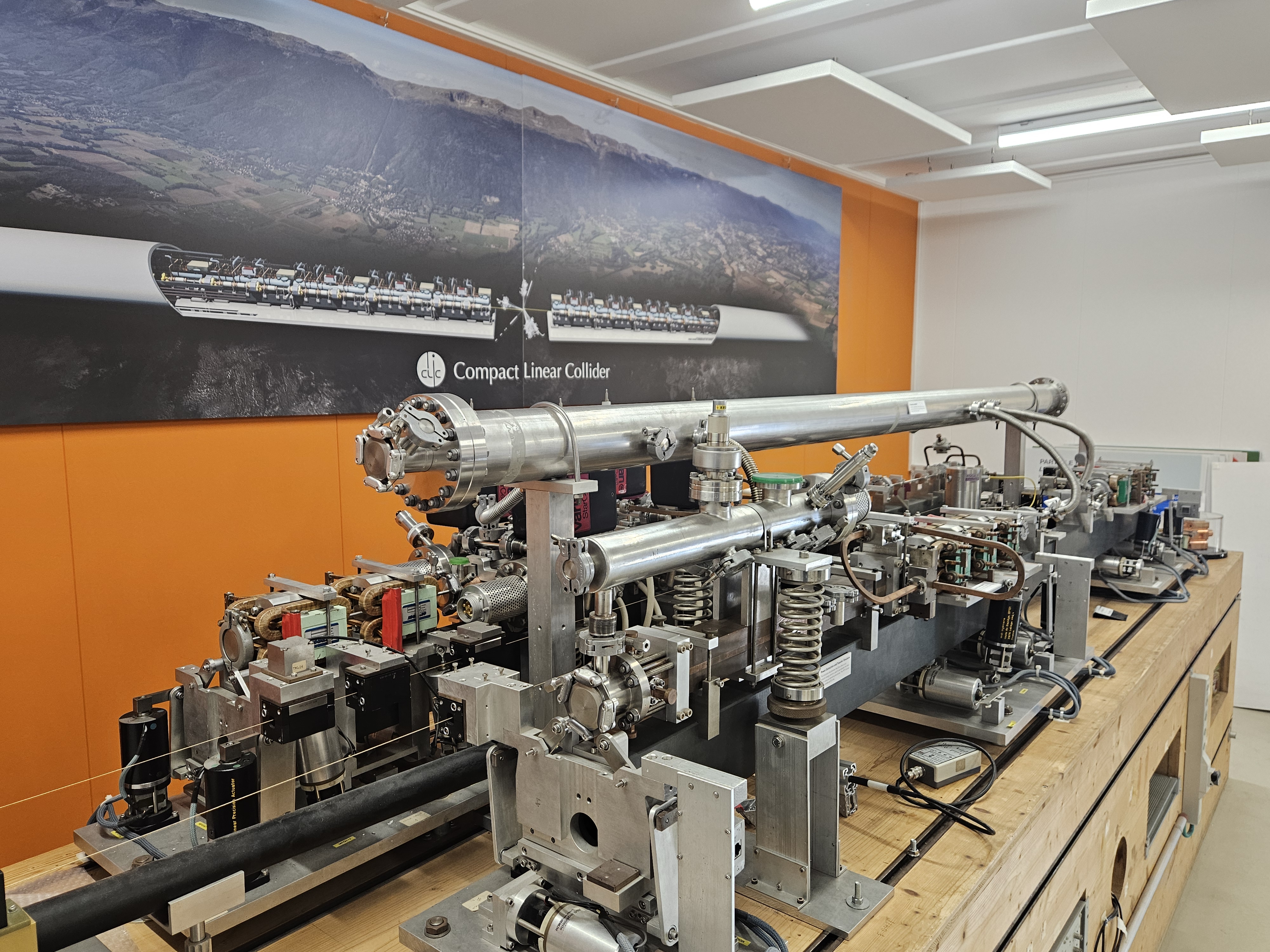

The Compact Linear Collider (CLIC) is studied as a next-generation high energy linear electron–positron collider to be built at CERN. Proposed already more than three decades ago, it has been designed to reach multi-TeV energies using a X-band (12 GHz) high gradient accelerator cavities and an innovative “two-beam acceleration” scheme capable of providing high and scalable radiofrequency (RF) power. The project has evolved from a conceptual idea into a mature design, supported by extensive prototyping, beam tests and industrial studies. CLIC is envisioned as a staged facility, starting at around 380 GeV for precision Higgs and top-quark physics, with upgrade paths to 1.5 TeV and possibly beyond to explore new physics at the highest energies.

What is the current status of the project?

CLIC completed its Conceptual Design Report in 2012 and its updated 380 GeV optimised design in 2018 documented in a Project Implementation Plan. The collaboration has consistently been advancing the design, performance and technology through targeted R&D, including high-gradient X-band structures, damping ring studies, beam delivery optimisation, and improved system integration. Key performance goals have been met in dedicated test facilities such as CTF3, FACET and CLEAR. Today, CLIC is in a “preparation and readiness” phase: technology is validated, cost and power estimates are mature, and the project is positioned as one of the options under consideration in the 2025-26 European Strategy process for a future collider to succeed the LHC. The collaboration has recently submitted comprehensive project descriptions and plans as input to this process.

What would CLIC allow us to explore in terms of physics?

At 380 GeV, CLIC would be a Higgs and top-quark “factory”, enabling measurements of Higgs couplings, rare decays and the top-Yukawa interaction with high accuracy. These data are essential for uncovering indirect signs of physics beyond the Standard Model. At higher energies - 1.5 TeV and beyond - CLIC enters the direct-discovery regime. It can search for new heavy particles, extended Higgs sectors, dark-sector portals, composite fermions and signatures of extra dimensions. The combination of clean e⁺e⁻ collisions, tuneable energy stages, and a polarised e-beam provides a wide physics reach within and beyond the Standard Model.

What are the main technical challenges?

The core challenge is achieving stable, reliable acceleration at gradients of ~100 MV/m in X-band structures over many kilometres. This requires ultra-precise manufacturing, high-power RF generation and good control of breakdown rates that could reduce the beam stability. Other key challenges include generating low-emittance beams in the damping rings, maintaining nanometre-scale beam stability over long distances, and delivering nanobeams to the collision point. The two-beam acceleration scheme, while demonstrated, must be industrialised at scale. Integrating power efficiency, seismic stability, alignment, and cost-effective civil engineering into a coherent design also requires good collaboration between accelerator physicists, engineers and industry.

Why does the scientific community need CLIC — and why now?

The discovery of the Higgs boson completed the Standard Model but left fundamental questions unanswered. Current experiments cannot resolve the Higgs’s role in electroweak symmetry breaking, the nature of dark matter, or whether new physics lies just beyond LHC reach. A precision e⁺e⁻ collider is the community’s highest global priority for addressing these questions. CLIC offers a mature, high-energy option that complements circular collider proposals and leverages decades of R&D. With LHC operations approaching their long-planned end in the 2040s, the community must choose its next flagship facility soon.

Who is behind the project?

CLIC is led by CERN but developed through a broad international collaboration spanning Europe, Asia and the Americas. More than 70 institutes and several hundred scientists have contributed to its accelerator design, detector concepts, physics studies and technology R&D. Key partners include national laboratories world-wide, university groups and industry. The CLIC Accelerator Collaboration and the CLIC Detector & Physics Collaboration have coordinated global efforts, ensuring consistent design, technology validation and detector development. This international framework builds on decades of shared expertise from LEP, SLAC linacs, ILC studies, Low Emittance Rings and FEL linacs.

What new technologies could emerge from CLIC that would benefit society?

CLIC drives innovation in several areas with strong societal impact. High-gradient accelerator technology enables cost-effective, compact, high-brightness linacs that can be used for imaging, high-precision radiotherapy, industrial irradiation, non-destructive testing and advanced X-ray and THz sources. Developments in ultra-stable alignment, vibration control and precision mechatronics can benefit aerospace, metrology and semiconductor manufacturing. Advances in power-efficient RF systems, klystrons and modulators support more sustainable accelerator infrastructures. As with previous accelerator projects, the technology base is likely to seed future industrial and medical innovation.